Building a Community in Brooklyn’s Backyards

In the regular patterns of Brooklyn’s street grid, there’s a slight deformity near Prospect Park that makes one block slightly larger than the ones around it. On this block of brownstones in Park Slope, the streets give the houses a little more breathing room for their backyards. And for more than three decades, the community here has gone one step further, turning that space into a sprawling private park of their own creation.

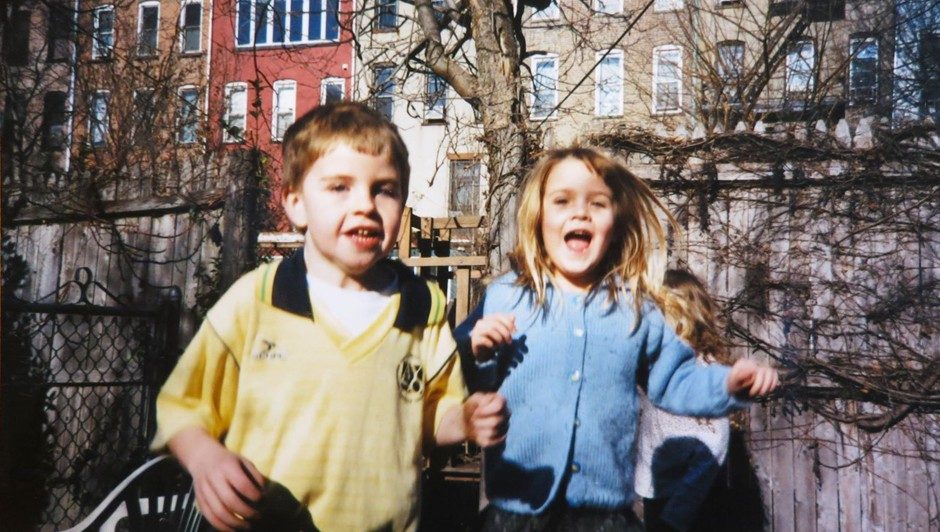

The result is a communal yard, divided only by unlocked fence gates. Playing here as a kid, it felt like magic—my own little corner of a city that’s not known for quiet spaces. With no streets or strangers to pose a threat, parents blessed their children with free rein of the space. It remains beloved today, especially in the warmer months, with the children lucky enough to live on the block running around in the yards—just as its creators hoped.

Back in 1983, Timothy and Sealy Gilles wanted a quicker way for their daughter to get to her friend’s house around the corner. “It was a pain in the neck to walk around the block to connect the kids’ playdates,” Timothy Gilles told me. The backyards were close, but divided by fences, which, as they do in most Brooklyn yards, serve to divide land and discourage entry. That’s why his family and another sought permission from their neighbors to connect the yards.

They faced few naysayers—only one person said no initially—and the process of making the space accessible was pretty straightforward. “It didn’t take much,” Gilles said, “[Putting up] several chain-link fences, some wood—it took two or three weekends.” Neighborly communication, two or three runs to Lowe’s, and a few weekends of work resulted in a backyard collective set to last for generations.

“When we were doing this, it was a different era,” he said. Park Slope wasn’t so tony then, not as lawyered up then as it is now; they didn’t seek legal advice before connecting the yards.

But the decades don’t make much difference when it comes to the most vital element of the operation’s success: being neighborly. “If someone were to want to do this [in their own community], then I would say, just reach out to your neighbors one by one,” Gilles advised. “Start with the houses next to you, then to the houses immediately behind you, and see how far you get in terms of getting people to agree.” Once you’ve got a small group in agreement over a backyard adjustment, go for it—others will see the project’s success and volunteer to join, he said. “People saw what was going on,” Gilles recalled of the yards’ early days, before all neighbors were included. “People like looking out their back windows and seeing all these kids having a great time.”

The shared space was made possible by a confluence of other factors beyond the control of most homeowners: The slight rotation of the grid at Garfield Street, which creates the wedge shape of the yards between it and Carroll Street; the density of children in the area, earning Park Slope the only partially endearing nickname of “Park Stroller”; the relatively high rate of homeowners; the neighborhood’s flavor of communal care at once aligned with and distinct from Brooklyn’s more general old-school neighborly energy. In my own backyard a few blocks away, the street grid is not on our side. I can walk halfway down the block from my roof, but the gardens don’t sync up, and it would take a far more permanent adjustment than the installation of a few gates to unite them.

My own experience in the yards came through my friend Alice Markham-Cantor. She lived on Carroll Street, across from our elementary school. After class in the early 2000s, we were allowed to walk home by ourselves: up the block, through the door beneath her stoop, across the bottom floor of the house, and out into the garden. Sometimes Alice’s neighbors were already outside, and we would wait for the round of hide and seek to end before joining in. Other times she had to assemble them, and we’d use a special call—more like a scream—to rally our playmates. “It’s made to sound like when you whistle with your fingers in your mouth, but it’s not, because none of us could do that,” said Maeve Kinney, Markham-Cantor’s neighbor. “It involves that roiling noise in the back of your throat. When I got my tonsils out at 12 I couldn’t do it for years.”

In the treehouse and among the laundry poles, we’d adventure, the children of the special stretch between Garfield Place and Carroll Street. “There was a whole secret area,” Kinney said of a corner of one yard, “it had nothing in it but weeds.” Then there was the crotchety old man who owned the treehouse. “He’d yell at us whenever we crossed the invisible border between his yard and Alice’s,” Kinney recalled, noting his unfriendliness was an exception among the neighbors. Kinney’s yard had a fig tree, still very much alive; the previous homeowner said it was brought over generations earlier on a boat from Sicily. “We’d have capture the flag tournaments that would last days,” said Markham-Cantor, who describes her memories of growing up in the space as “the childhood endless summer.” Thinking of her youth in the yards makes her smell honeysuckle and raspberries, she says, “and the sense of having the whole summer night stretching out. The sense of possibility—it’s a magical place.”

There were rules in the yards, which must’ve been spoken at some point, but were silently understood and obeyed by all when I began playing there. Wait for the raspberries to get ripe, and pick them together. Two people in the treehouse at a time. Don’t tread on the delicate flower beds. Certain yards were accessible, but off limits. The atmosphere was one of a commons for children, and at the end of the day, so long as those deemed responsible babysat the youngest kids, the parents let us be. “This is a little slice of how every child should be able to grow up—with freedom to roam in nature, and easily accessible playmates,” said Markham-Cantor’s mother, Laura Markham.

Kinney credits the yards’ magic to the way they were brought together. “It was mostly just the fact that the backyards were built the way they were, with the fences. Two full rows of yards on Carroll Street and Garfield that magically connected.” She said the yards hit a peak during our youth, due to what Markham-Cantor described as a “critical mass of kids.” Both Timothy and Sealy Gilles, however, say today they see roughly as many children out in the yards during the warmer months as there were then, same as it ever was.

Today, the Carroll Street and Garfield Place backyards are still there, still accessible, but some physical highlights are gone. The treehouse is no more. It seems some of the magic has been stripped by the broader changes in the neighborhood. At the beginning of the millennium, Park Slope was nice, but property values have since skyrocketed along with the rest of Brooklyn. In 1982, a year before the yards’ birth, The New York Times reported that Park Slope newcomers were driving up the price of area brownstones “past the $200,000 mark.” Today, the only Park Slope properties among the Times’ sale listings within $100,000 of that are parking spots.

For many homeowners on the block today, the opportunity for rental income is difficult to pass up, and one house has become something of a rotating door for wealthier international tenants who’ve tended to keep their distance. Markham-Cantor and Kinney, who’s families both still live on the block, believe the magic is alive and well—but the quick turnover of residents, some with children and some without, depletes it.

Revisiting the yards to write this article, it was difficult to gauge how the soul of the space had evolved. The Gilles and I were alone in the back on the day I visited. They pointed out the small things that had changed since I’d been there last: a tree had died, a chicken coop had been installed, some extensions and renovations had been made to the homes. It all looked small compared to my memories, but there was a certain glory in it still being here at all. Just up the block, on 7th Avenue, I’d watched helplessly as the cluttered shoe shops and Italian bakeries of my youth slowly gave way to more high-end establishments far less prone to the atmosphere of discovery I’d enjoyed in their predecessors. But this protected garden space lived on. In as ever-changing a borough as Brooklyn, knowing a place that brought me so much childhood joy remains cherished, protected, and in little danger of development is something of a miracle.